Introduction:

Incentives Matter

Prague University of Economics and Business

Faculty of Informatics and Statistics

Introduction

Contact Info

Instructor: Paulo Fagandini

📧 : pfagandini@iscal.ipl.pt

🌐 : pfagandini.github.io/prague_economics_incentives

Core Bibliography

📖 The bibliography will be given at the end of each section. Sometimes it will cover a book chapter, and sometimes it will be an academic article.

Assessment

The course will have 4 assessment activities.

- 2 Quizzes, worth 10% each.

- 1 Problem Set, Individual, worth 30%.

- 1 Exam, worth 50%.

Quizzes

The quizzes will be multiple choice, and will cover the in-classroom lectures and discussion.

These quizzes are closed-book.

Problem Set

The problem set will be a list of suggested exercises. You can solve these with your colleagues, however you need to deliver your own individual and unique solution.

For the problem set, you are allowed to use LLM tools to help you along the way. However, it is not allowed to use LLMs to produce the final deliverable, this must be your own work.

Problem Set

Solutions can be delivered using

- MS Word or equivalent.

- LaTeX

- Markdown/Quarto

While the last two methods are prefered, there is no bonus or penalty in case you choose to deliver using another software.

Exam

The exam will consist of two main parts:

- First half (worth 50% of the Exam grade) of qualitative questions, in the form of “discuss this” or short essays questions. They can refer the mathematical models, but are mostly focused on applications or reasoning on the motivations of the models.

- Second half (the other 50% of the Exam grade) of quantitative questions. These will resemble the suggested exercises on the problem set and the models developed in class.

Incentives in Real Life

Dynamic Inconsistency

Crypto regulation

Auctions / Competitive Tender

Governments can use auction theory to reduce cost of material or service sourcing, and the construction of bridges and stuff.

Adverse Selection

Market for lemons in clear energy markets.

Getting the Playground Ready

Rules of the Game

For any game we want to model, we will need to define some components:

- who is playing. (players)

- what are they playing with. (actions, strategies)

- when each player gest to play.

- how much they can gain or lose. (payoffs)

- Further, we assume players are equally informed about these rules.

Representation of a game

- Extensive form

- Normal (or Strategic) form

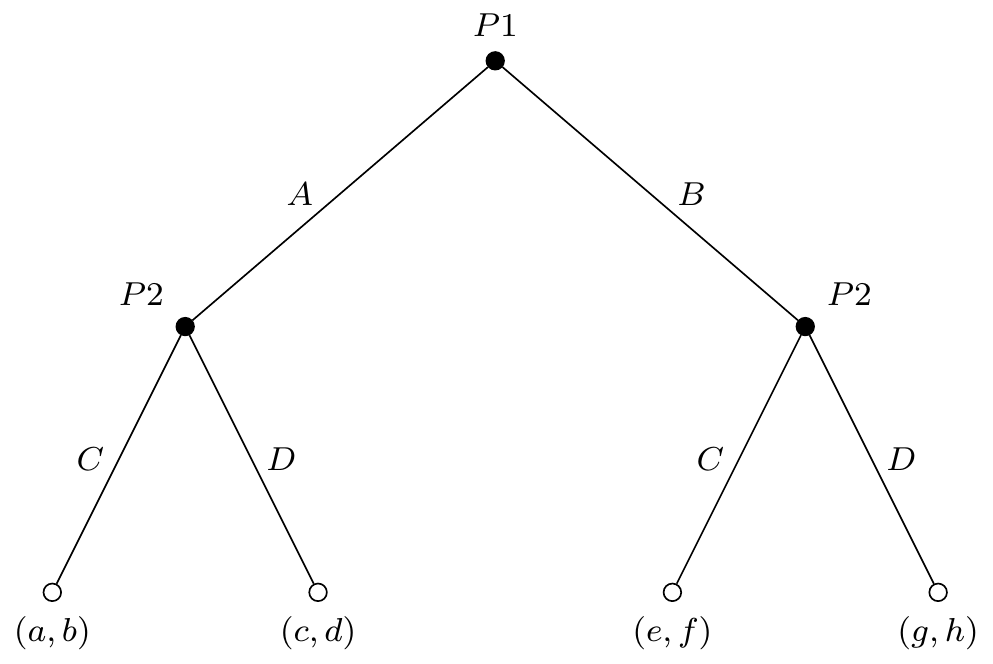

Extensive form

Action

At every node, the player will have to chose an action. In the previous figure, we can see this represented as each branch that originates in every node.

For example, player 1 (P1), who plays first, has, at that moment, actions \(A\) and \(B\) available.

Strategy

Each player has a strategy that dictates an action in each decision node. Say a plan that tells the player what to do in every possible situation she finds herself in the game. For \(P2\) we would have \((CC)\), or \((CD)\), or \((DC)\), or \((DD)\).

A strategy profile will be an ordered pair of strategies for each player, i.e., a vector that contains a strategy for each player. For example here, we could have \((A,(CD))\), which would say that player 1 choses \(A\), and player 2 choses strategy \((CD)\).

Timing

There are two main ways in which a game can be player (or a turn can be played).

- Simoultaneously

- Sequentially

For the second case, the extensive form is the most intuitive way to represent a game. For simoultaneous games, the Strategic form is more adequate. Let’s move to this game representation.

Strategic form

When using the strategic form, we represent a game with a table, where rows and columns represent strategies for each player. The cells in the table will contain the payoffs. Because convention, we place the first player on the left, with her strategies in rows, and the second player on top, with her strategies represented in the columns.

Payoffs will be represented again as an ordered pair, where the first coordinate contains the payoff for the first player, while the second coordinate contains the payoff for the second player.

Strategic form

| P1 \(\setminus\) P2 | \((CC)\) | \((CD)\) | \((DC)\) | \((DD)\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(A\) | \((a,b)\) | \((a,b)\) | \((c,d)\) | \((c,d)\) |

| \(B\) | \((e,f)\) | \((g,h)\) | \((e,f)\) | \((g,h)\) |

Clearly, strategic form games, make more sense for 2-player games.

Representing a game

Not all games are worth representing in either one of these two ways. Some games, specially those with continuous action space (so far we saw discrete action spaces) might make the attempt to represent the game futile. We will study these games in the future, but in these cases, we will also be able to use a utility function to find out which strategy would deal the highest expected utility (payoff) for the player.

Economics of Incentives